The life and journey of Fernando Zobel de Ayala as an expat and artist in the United States and Spain.

In the Philippines, the name Zobel de Ayala is almost synonymous with the Makati urbanscape. Few know that one Zobel, born in Ermita, Manila in 1924, made a name, not in real estate but in the field of arts and letters. “Made a name” is rather imperfectly prosaic.

Fernando Zobel de Ayala y Montojo Torrontegui’s memory is celebrated in heroic proportions in Spain. A high-speed train station and a secondary school are named after him. In 1983, King Juan Carlos I awarded him the Medalla de Oro al Mérito en las Bellas Artes. No other Filipino artist has been awarded with two retrospectives by two of Spain’s premiere museums, the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía in 2003, and Museo del Prado, which is currently exhibiting “The Future of the Past’’ with his works until March 2023.

Zobel de Ayala’s expat life

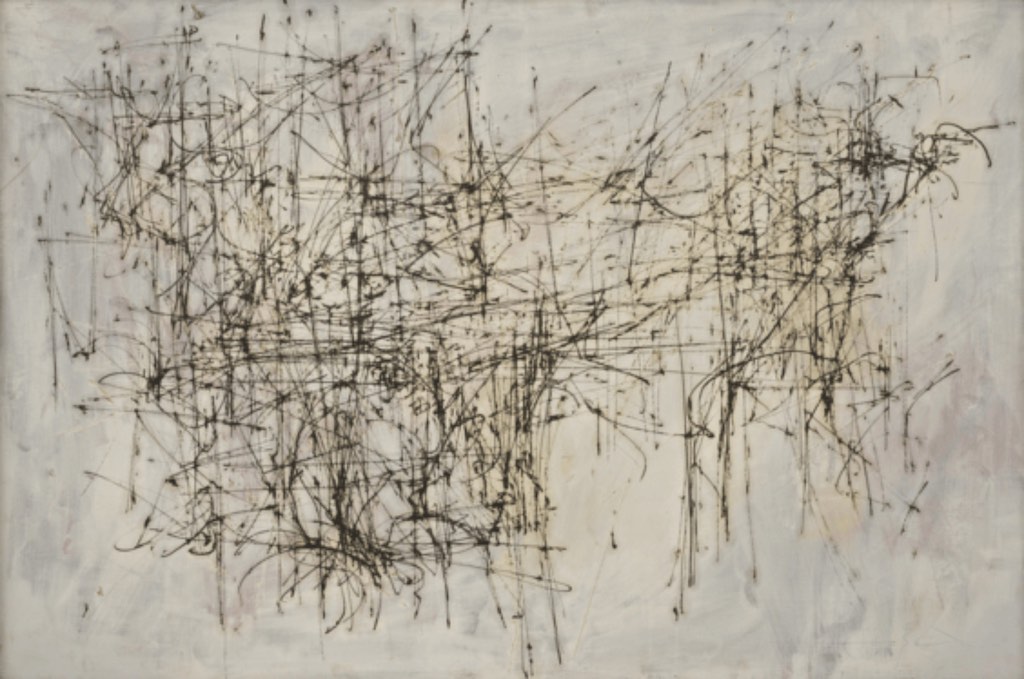

Zobel’s life as an expat had taken both focused and serendipitous twists. The man, whose artwork Hattecvm was sold at a Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction in 2013 for P43 million, did not begin as world caliber.

The birth of the Zobel high art was morosely somber. After graduating high school in Baguio in 1940, he enrolled at the University of Santo Tomas for preparatory medicine but the invading Japanese would soon turn UST into a war camp.

He had been suffering from a spine problem since childhood. Confined at the National Orthopedic Hospital, he was confronted with his first horror vacui.

“For a whole year, I was bedridden. I had all the time in the world to think and it was then that I started to consider the idea of becoming an artist.”

Fernando Zobel de Ayala, 1972

Then the Japanese army seized the Zobel home in Manila and the family was forced to seek refuge in the Batangas countryside.

“It was as if, all at once, the clock had stopped ticking. There was nothing to do.” The family not only waited out the end of war, but soon a tragedy lay in wait. His father, Enrique Zobel de Ayala died in 1943 when the young Fernando was only 19 years old.

The worlds of painters and writers

When the war ended, Fernando left Manila to study Humanities at Harvard University. Arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he bought himself a box of oil paints. He had no formal art training but was being pulled by the two worlds of painting and writing. In the summer, he read Federico Garcia Lorca and translated Amor de don Perlimplin con Belisa en su Jardin. The manuscript with Zobel’s caricatured drawings is now at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

At the end of 1946, he met painter Reed Champion and her husband, Harvard fine arts professor, James Pfeufer. He became a novice under their guidance. But of the paintings that he had produced from 1946 to 1949, only two survived. He destroyed most of them, haunted perhaps by the insecurity and uncertainty of being a novice artist.

In 1949, he graduated with a dissertation on Spanish poet and playwright Garcia Lorca and was awarded the Latin honors of magna cum laude. He returned to Manila after graduation, but Harvard beckoned. He went back to the US on the pretext of enrolling at Harvard Law School, only to quit and work as assistant to the curator of Harvard College Library’s Department of Graphic Arts.

The job introduced him to engraving and experimenting with pen, etching, dry point, boxwood engraving and xylography. The fundamental Fernando Zobel had taken shape. His paintings at this time had connotations of fierce social criticism and satire. He exhibited his first two collective exhibitions at Boston’s Swetzoff Gallery that year, and in the next, his works were exhibited alongside those of Klee, Chagall, Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso and Cézanne.

After holidaying in Spain, he returned to Manila to start work at Ayala y Compañia. It was at this time that he developed close friendships with artists Arturo Luz, H.R. Ocampo, Anita Magsaysay Ho, and Vicente Manansala. In 1953, he was elected president of the Art Association of the Philippines, signaling his full integration into the Philippine art world.

On a trip to the US in 1955, the Rhode Island School of Design invited him to stay as a resident artist. Abstract expressionism was then trendy in the US. The works of Mark Rothko, the Latvian-born American abstract expressionist, bedazzled him. Rothko’s works were “huge, horizontal blotches of color completely flooding the canvas.” A mesmerized Zobel would visit the Rothko exhibition at the Providence Museum everyday. He began to paint along the Rothko style.

In Manila, he taught art history for a year at the Ateneo de Manila. Spain appointed him Honorary Cultural Attaché for its Manila embassy in 1956. He used the position to obtain scholarships to Spain for Filipino artists Arturo Luz, Cesar Legaspi, José Joya, and Nena Saguil.

The hanging houses of Cuenca

In 1958, he moved to Madrid and opened a studio on Calle Velázquez 98, later on Calle Fortuny 12. He formed friendships with artists Gerardo Rueda Salaberry, Antonio Saura, Eusebio Sempere, Martin Chirino, and Antonio Magaz. The turning point was imminent: he began collecting Spanish abstract paintings. In 1962, he began to plan what he called the “Toledo Project” — what to do with his rapidly growing collection and where to house them.

Together with Rueda, he went to Toledo in 1963 in search of a place for the collection, but they found nothing pleasing. His friend Gustavo Torner, Spanish painter and sculptor, invited him to the city of Cuenca. There, something developed. The mayor of Cuenca offered him the Casas Colgadas as a possible home for his future museum.

The spectacular Las Casas Colgadas – Hanging Houses – is a series of 500-year old houses perched on a towering cliff overlooking the Huécar River. Zobel was instantly taken.

He wrote to his American friend Paul Haldeman in 1963: “My big project is a Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in the city of Cuenca, two and a half hours from Madrid, in the renowned ‘Hanging Houses’ which the kind- hearted, forward-looking mayor has let me rent for thirty years at something like 1.50 dollars per annum.”

The Museo de Arte Abstracto Español, inaugurated on 30 June 1966, was Zobel’s magnificent obsession to provide a home for Spain’s abstract artists. It was a pioneering initiative – until the 1980s, Spain barely housed contemporary arts in a standard museum setting.

The museum attracted international media attention, eliciting articles in Time Magazine, Architectural Forum, Herald Tribune, and other prestigious magazines and newspapers. In 1978, a library specializing in Spanish contemporary art was added. Two years later, Zobel donated the entire museum to the Fundación Juan March. The grateful city of Cuenca named its secondary school the Instituto Nacional de Bachillerato Fernando Zobel.

On a trip to Rome in June 1984, Zobel died from a heart attack. His remains were brought to Cuenca and buried at San Isidro cemetery, a narrow pass overlooking the Huecar River. Cuenca posthumously awarded him its Medalla de Oro de la Ciudad.

In 1996, UNESCO inscribed the medieval fortress town of Cuenca as a World Heritage Site, including the famous Casas Colgadas, “for its outstanding universal value as an exceptional example of a preserved original townscape remarkably intact.”